Trip Hawkins - 3DO visionary

Trip Hawkins: Visionary Game Executive who helped build and break the Rules of Interactive Entertainment

Introduction: The Maverick Behind the Game Console Wars

Few figures in the tech and gaming industries are as polarizing or pioneering as Trip Hawkins. From building the early marketing strategies at Apple to founding the iconic Electronic Arts, Hawkins helped shape the video game industry’s business, culture, and technological growth. His career is a study in vision, ambition, and the volatile marriage of innovation and commercial risk.

Early Career: From Apple’s Core to Entrepreneurial Dreams

Born William M. Hawkins III on December 28, 1953, in Pasadena, California, Trip Hawkins earned his undergraduate degree in Strategy and Applied Game Theory from Harvard and later received an MBA from Stanford. His academic interests laid a firm foundation in understanding the intersection of entertainment, business, and digital interactivity.

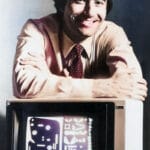

Hawkins joined Apple in 1978 as one of its first marketing executives. There, he worked closely with Steve Jobs and played a role in developing the Lisa and Macintosh product lines. While at Apple, he began sketching out his vision for a company that would treat software, particularly video games, as a serious art form and business.

Electronic Arts: Reinventing Games as Art and Business

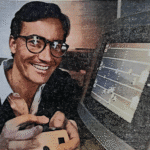

In 1982, Hawkins left Apple to found Electronic Arts (EA), with a radically different vision from traditional software companies. EA was one of the first to market game developers as “software artists,” even placing their names and images on game packaging—a practice rare at the time. Hawkins was annoyed by Sega’s expensive licensing plans and set his team a task to successfully reverse engineer a Sega Genesis dev kit he acquired. Threatening to by-pass Sega and publish Genesis games directly he managed to negotiate a far better publishing deal than any other developers had before. Under his leadership, EA went on to publish landmark games such as John Madden Football, Archon, The Bard’s Tale, and Populous, cementing its reputation for high-quality, cutting-edge titles.

EA wasn’t just about games—it was about changing the entire industry model. Hawkins pioneered relationships with developers and aggressively advocated for game studios to retain some degree of creative ownership and credit. This approach, which won early loyalty from developers, evolved into a more corporate structure as EA scaled, eventually leading to criticism from some in the developer community in later years.

The 3DO Gamble: Ahead of Its Time—or just Misaligned?

In 1991, Hawkins stepped down as EA CEO to launch The 3DO Company, which aimed to revolutionize the home console market with a multimedia system that would eclipse the likes of Sega and Nintendo. The 3DO console, released in 1993, was technically advanced but came with a steep $699 launch price and a licensing model that failed to attract enough quality titles or third-party support.

Despite significant industry buzz and support from companies like Panasonic, the 3DO was a commercial disappointment. It highlighted Hawkins’ forward-thinking vision—CD-based media, modular platforms, and online connectivity—but also his vulnerability to misreading market readiness and consumer price sensitivity. By the mid-1990s, the 3DO was discontinued, and the company pivoted to software development before dissolving in the early 2000s.

Later Ventures: EdTech and Mobile Gaming

Not one to shy away from innovation, Hawkins continued to push boundaries. He launched ventures such as Digital Chocolate in 2003, focusing on mobile games long before the App Store revolutionized the sector. Digital Chocolate found success with titles like Tower Bloxx and Millionaire City, though it too struggled with scale and competition from newer players like Zynga and Rovio.

In more recent years, Hawkins turned his attention to educational technology and gamified learning platforms. His efforts in this space reflect his long-standing belief that games can be powerful tools for learning, engagement, and behavioural change.

Legacy: Bold Moves, Contested Impact

Trip Hawkins’ legacy is as complex as the industries he helped shape. He was a champion of creative expression in video games, an architect of one of the most powerful gaming companies in history, and a bold technologist unafraid to take big swings—even when they missed.

His influence is undeniable: EA remains a dominant force in global entertainment, and many of the models he pioneered—celebrity-endorsed sports franchises, serialized gaming, mobile microtransactions—have become cornerstones of the industry.

Conclusion: A Disruptor in Perpetual Beta

Trip Hawkins might not have had a perfect track record, but his contributions helped professionalise and legitimise an industry once dismissed as a hobby. He’s a reminder that tech’s most transformative figures are often those who dare to leap before the market is ready—and whose failures can be just as instructive as their successes.

In an era dominated by iterative improvements and safe bets, Hawkins stands out as a symbol of risk-taking and relentless belief in the potential of digital interactivity