Starblade 3DO review

Genesis of Starblade

Galaxian 3 – a massive space opera

Starblade’s roots lie in 1990 with Galaxian3: Project Dragoon, a groundbreaking arcade experience for Expo 90 Osaka. This colossal rail shooter utilized a dual laserdisc technology, overlaying vibrant polygons onto pre-recorded footage. Supporting up to 28 players simultaneously, Project Dragoon was initially a theme park sensation, finding a permanent home at Namco Wonder Eggs before embarking on a global tour as a 6-player cooperative experience using the higher quality Theater 6 system.

Players assumed control of the Dragoon, a massive spacecraft tasked with defending the galaxy from the insidious Unknown Intellectual Mechanized Species (UIMS). The action unfolded along a predetermined path, with players manoeuvring a coloured cursor to obliterate enemy forces. The Dragoon’s energy reserves dwindled with each enemy hit, demanding strategic precision and teamwork.

I remember playing the 6-player version of Galaxian 3 at Trocadero Funland in London before it closed. The game looked amazing and required cooperation from all players to reach the final boss.

The Rise of Starblade arcade

In 1991, Namco leveraged its cutting-edge System 21 hardware to bring Starblade to arcades. While retaining the core gameplay and storyline of its predecessor, Starblade transitioned to a single-player experience. Developed under the guidance of Hajime Nakatani, with a captivating soundtrack by Shinji Hosoe, Starblade introduced a unique visual spectacle. Namco employed a large concave mirror system within the arcade cabinet, creating a sense of depth and immersing players in a panoramic 3D experience.

Starblade 3DO

Console versions – 3DO

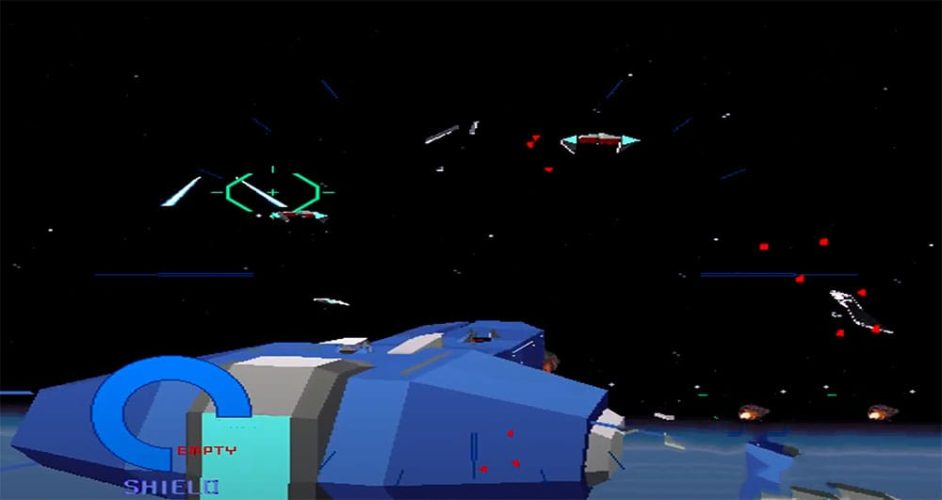

Starblade’s journey to home consoles began in 1994 with ports for the Sega CD utilising basic wireframe ships and then 3DO. The 3DO version offered a unique twist: a choice between the original arcade-style flat polygons and a groundbreaking new rendition featuring textured mapped polygons. This “next-gen” presentation significantly enhanced the game’s realism, providing 3DO owners with a tangible point of differentiation.

Control Concerns

Despite its visual prowess, Starblade’s controls proved to be a point of contention. The aiming cursor moved sluggishly across the screen, adding an unexpected layer of difficulty. Fortunately, the game generously provided numerous continues, including an unlimited continues cheat (Up, Right, Down, Left, A, B, C, Up, Left, Down, Right) and a super rapid-fire option (Up, Up, Down, Down, Left, Right, A, A, B, B, C, C).

Replay value

With these cheats, completing Starblade in under 30 minutes was entirely feasible. However, this brevity exposed a significant flaw: a lack of substantial replay value. Once the credits rolled, there was little incentive to revisit the experience. The absence of power-ups and the inability to steer the Geosword battleship further limited player agency.

A 3DO Triumph

Despite these shortcomings, Starblade remains a testament to the 3DO’s technical capabilities. The textured mapped polygon option was a groundbreaking feat for 1994, offering a level of visual fidelity unmatched by its contemporaries. Starblade, with its intense on-rails action and immersive presentation, provided a thrilling, albeit fleeting, arcade experience for home consoles.

3DO gameplay

3DO Starblade screenshots

Starblade 3DO game box

Galaxian 3 promo

Starblade arcade promo

Starblade CVG Review

Starblade 3DO: Key points

- Galaxian 3: Project Dragoon:

- A massive arcade rail shooter utilizing laserdisc technology.

- Supported up to 28 players simultaneously.

- Players controlled the Dragoon spacecraft to defend against the UIMS.

- Required teamwork and strategic precision.

- Starblade Arcade:

- Developed using Namco’s System 21 hardware.

- Single-player experience with a focus on visual spectacle.

- Employed a large concave mirror system for immersive 3D visuals.

- Starblade 3DO:

- Ported to 3DO with a unique textured mapped polygon option.

- Offered a significant visual upgrade compared to other versions.

- Controversial controls due to sluggish cursor movement.

- Limited replay value due to short length and lack of significant gameplay elements.

- Starblade: Operation Blue Planet:

- Planned sequel for System 246 with the “Over Reality Booster System.”

- Showcased at AOU 2001 with impressive but ultimately unfulfilled potential.

- Never released due to high production costs.

Starblade manual

Operation Blue Planet

Starblade’s forgotten sequel

Starblade: Operation Blue Planet was meant to be a sequel to Starblade destined for the new System 246 board, but not just in any old cabinet. This was to be a sensory assault featuring the “Over Reality Booster System” (O.R.B.S.), a monstrosity of a machine.

It had a vibrating seat, a dome-shaped screen enveloping you, and blasts of air were timed to in-game events. This wasn’t just meant to be a game; it was an experience. It was showcased in the 2001 AOU show in Osaka where it attracted 75-minute wait times.

However, Operation Blue Planet was never released due to the high production costs